Zero waste: the fish, the whole fish and nothing but the fish

Historically less than half of a fish by weight was seen as having value, but that is all changing.

The Iceland Ocean Cluster – an industry grouping bringing together more than 70 companies and entrepreneurs in the seafood sector – estimates that globally, around 10 million tonnes of targeted, commercially caught fish is thrown away every year.

This waste either goes back into the ocean, where it can disrupt marine food webs, or it is deposited in landfill sites, creating methane – a greenhouse gas that contributes significantly to global warming.

Waste is a problem for fish farmers as well as the catch fishing industry, so not surprisingly there has been a lot of interest around the world in the “100% Fish” programme launched by the Iceland Ocean Cluster.

The Cluster was created in 2011 and it very soon began to focus on the waste issue. A key driver for this was the reduction in cod quotas over recent years, to ensure stocks are not depleted.

Iceland typically produces between 200,000 and 250,000 tonnes of cod annually. It’s the country’s biggest seafood export, so increasing the value from each fish caught has become a priority.

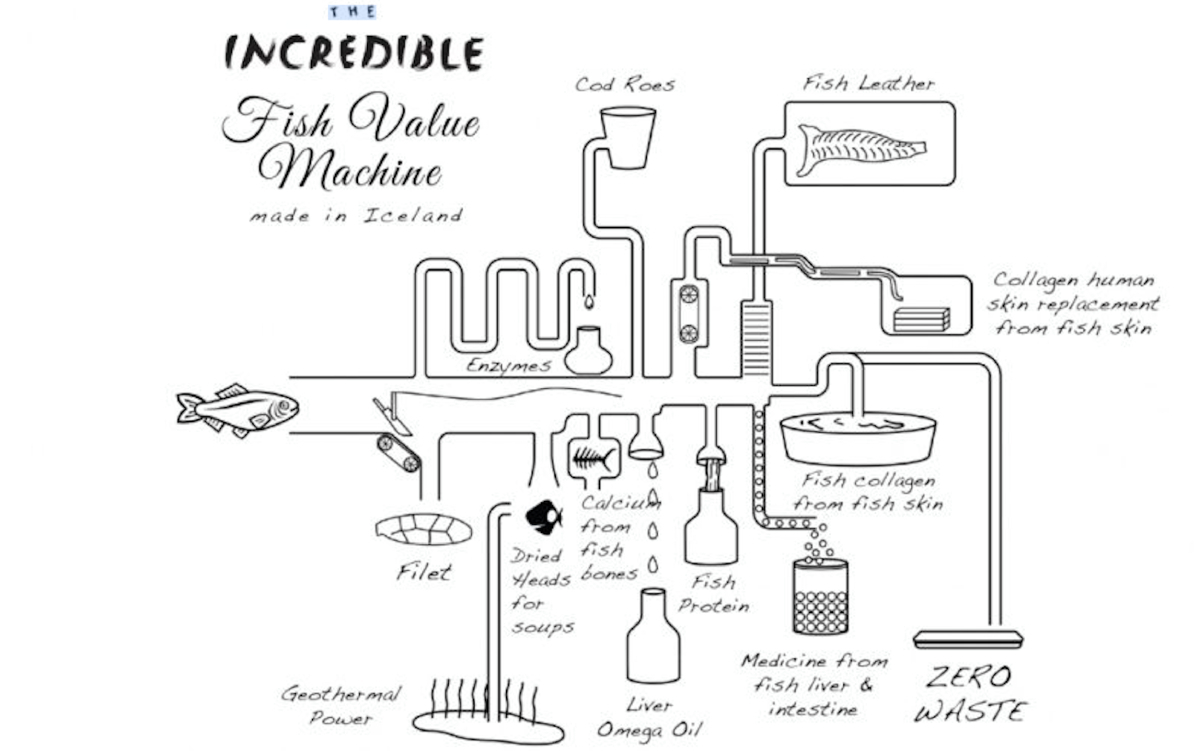

The cod fillet – once seen as the only element with real value - accounts for around 45% of the fish by weight. Now, however, Iceland’s processors are finding value in as much as 90% of the fish. The Cluster estimates that a fish once worth an average of $12 (around £10) could now have a potential value of up to $5,000 (just over £4,000).

Dr Alexandra Leeper, CEO of the Iceland Ocean Cluster, says: “We always say that crisis drives innovation. We knew we couldn’t keep fishing at the scale we were, so the question was how can we do more with less, so that we do have fish for the future and this sector can retain its core economic role.”

One of the key roles for the Cluster was to bring the players – producers, processors and end users – together. As Leeper explains: “These groups were not in much contact before because they hadn’t needed to be. There was a dialogue gap.

“A lot of the work that the Cluster did right at the beginning… was bringing the managers of all the fisheries companies together with the fish processing and the technology companies, and allowing them to actually sit at the same table and talk, and to build trust.”

The initiative started by identifying “low hanging fruit”. Simply improving processing and storage with more automation was a relatively quick win.

Identifying potential new markets was another important task. Fish heads are removed during processing and, in Iceland, these were typically thrown out as waste. As it turned out, however, there was an existing market for dried fish heads – Nigeria, where dried fish heads are a key ingredient for a traditional stew.

Another important market was health supplements. Cod liver oil is a traditional product, but by working with biotech businesses to develop processing techniques, the cod sector was able to use cod liver far more efficiently.

Now, cod by-products are being used for everything from pet food to collagen for advanced biomedical applications – and fish skin is tanned to create an incredibly thin, strong form of leather.

Spreading the word

The industry in Iceland is now working with the fishing industries of other countries, and with other species, to apply the principles developed in Iceland’s cod sector.

In North America, the Iceland Ocean Cluster is working with a regional initiative led by the Great Lakes St Lawrence Governors and Premiers (GSGP), a body that includes state and provincial bodies in the USA and Canada. So far 36 regional companies have signed the “100% Great Lakes Fish” Pledge, committing to using 100% of each commercially caught Great Lakes fish – which entails finding suitable solutions for a wide range of species – by the end of this year.

Similar initiatives are underway in the Pacific islands and in Oregon. Meanwhile, in southern Africa, the Namibia Ocean Cluster has been set up to apply the approach to the country’s Marine Stewardship Council-certified hake fishery to develop a plan for “100% Hake”. The idea is to find better ways to use the significant portion of hake that is thrown overboard before landing.

Meanwhile, the Iceland Ocean Cluster is also looking at applying the principles to other species. Alexandra Leeper gives an example: “We’re working with Royal Greenland right now on a really wonderful project we’re calling 100% shrimp, but it’s under the same banner of 100% fish thinking.

“We’re looking at how does a big company – Royal Greenland is the biggest producer of cold water shrimp – make these transformations and create more value, in this case, from shrimp shells.”

The Scottish dimension

In Scotland there has been a great deal of interest in the Icelandic waste reduction and 100% fish utilisation programme. As Donna Fordyce, Chief Executive of industry body Seafood Scotland, explains, a steering group has already been set up to map out what a Scottish Seafood Cluster would look like, after being inspired by the progress Iceland and other countries have made in this field.

Members include Seafood Scotland, Zero Waste Scotland, IBioC (the Industrial Biotechnology Innovation Centre), Aberdeenshire Council, and Opportunity North East (a private sector economic development body).

Fordyce says: “There has been a lot of interest from the sector. We are looking to clarify what volumes of seafood are being processed in Scotland and this work is being supported by the UK body Seafish and the Marine Directorate of the Scottish Government.

“We are also looking to see what technologies are already out there in Scotland and where the gaps are. The aim is to foster collaboration and innovation among entrepreneurs, industry leaders, and identify and create market opportunities.”

The aspiration is to source funding for a dedicated project manager to drive this forward and connect the industry, innovators and other stakeholders, as well as a space for the Cluster to operate from.

Fordyce stresses that Scotland has a number of advantages besides its well-established seafood sector – the country is strong in science, including marine and life sciences, and it enjoys a well-connected entrepreneurial network.

One Scottish seafood business has already acted on its own account, in a case study that also highlights connections with aquaculture. Lunar is a family-owned business based in Peterhead, on Scotland’s east coast. The group owns whitefish and pelagic fishing vessels and processes this catch for direct human consumption in their own factories in the port.

In 2022 the Lunar board decided to build its own fish meal/fish oil facility, which achieved certification to the MarinTrust factory standard in 2023. This certification provides assurances around the responsible sourcing, production and traceability of marine ingredients (fish meal and oil) and is stipulated within the sourcing policies of feed producers, pet food manufacturers and retailers.

Lunar provides haddock, mackerel and other seafood species for the retailer Marks & Spencer (M&S), which itself stipulates that all its fish and seafood is responsibly sourced, in line with its rigorous “Forever Fish” policy.

Further, the by-product from this is further processed into fish meal and fish oil, which goes to aquafeed business BioMar in Grangemouth, central Scotland, to be manufactured into feed for use by salmon farmer Scottish Sea Farms, which supplies salmon to M&S.

The arrangement means that the whole cycle operates with a very short, local chain. As well as entailing a smaller carbon footprint, this helps traceability – which is important to M&S as the corporate customer – and also, importantly, retains more nutrients in the oil and fishmeal, making it a better feed ingredient for the salmon.

Libby Woodhatch, Executive Chair at MarinTrust, says: “We’re seeing greater interest in trimmings. It’s fish that’s already caught, so it makes sense to fully utilise everything that’s being landed.”

In terms of MarinTrust standards, the important issue is that the by-products (fish trimmings) as well as whole fish can be shown to be from a verifiable source, i.e. a fishery managed according to FAO’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, with no IUU (illegal, unreported and unregulated) materials, and industry practices at the factory level aligned with local environmental and social regulations.

Woodhatch says: “It’s about making sure that by-product coming into a factory that is going to be audited [for the Trust’s certification] can be assessed and approved. We make sure that it’s traceable.”

It’s the kind of “circular” thinking Seafood Scotland would like to encourage more widely in the industry.