Ten years on

Scotland’s seaweed industry is celebrating 10 years since its association was founded, but at its annual conference the emphasis was on the future.

Where will we be in 10 years? This was the question posed as the theme of this year’s Scottish Seaweed Industry Association (SSIA) conference. Despite the temptation to celebrate how far the industry has come, the focus was on where it could go next – and how.

The conference was once again held in Oban, on Scotland’s west coast, and it attracted attendees not just from across Scotland but from the rest of the UK, Ireland and further afield.

Rhianna Rees, Business Development Manager, opened the event with an update on what the SSIA is doing to help develop the industry – including working with UK-wide authorities to get a joint policy on growth and a common approach to issues such as the European Union’s import regulations.

Mairi Gougeon’s video address

Mairi Gougeon, Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs, Land Reform and the Islands, was the keynote speaker – via video – for the first morning, and she took the opportunity to deliver a ringing endorsement of the seaweed industry.

In 2022, when the statistics were last compiled, the Scottish seaweed sector had an estimated yearly turnover of around £4m, and an estimated GVA of £510,000, employing 59 people.

Mairi Gougeon said: “In 10 years’ time we fully anticipate that the sector will be a major contributor to Scotland’s economy, along with finfish and shellfish.

“Up until now, the sector has been dominated by wild harvesting, but this is changing - I’m pleased to be able to tell you that we currently have 19 live marine licences and 13 marine licence applications for cultivating seaweed, mainly kelp, a species which does extremely well in our cool northern waters.

“This is an exciting time for seaweed cultivation, with increased growth and diversification, and the development of new innovative products.”

The Minister highlighted ways in which the Scottish Government is supporting the sector, including grants to help establish seaweed farms and processing facilities, and funding for Rhianna Rees’ post as Business Development Manager.

She went on: “One of our greatest challenges is climate change. There is no doubt now that population growth and increasing pressures on our natural environment are causing unprecedented global events, with changing weather patterns causing devastating flooding and drought.

“We know that the transition to net zero emissions is crucial to addressing these pressures, and that seaweed cultivation forms an essential part of our green recovery. We are ready to play our part.”

She concluded: “The Scottish Government has every confidence in Scotland’s seaweed growing and harvesting community, which is a community of innovators in an industry which is playing a very important part in our greener, more sustainable future.”

Biostimulants and agriculture

The first panel discussion addressed the role of seaweeds as a way to make terrestrial agriculture more effective. The use of seaweed as a simple fertiliser is long established, but this is fairly low down the chain compared with seaweed as a biostimulant.

“Biostimulant” is a flexible concept, but essentially it is a resource that helps plants to overcome stresses and perform better. A particular biostimulant can help crops to face challenges such as drought, excess water, pests and diseases.

As Dr Gordon McDougall, Head of Plant Biochemistry and Food Quality at the James Hutton Institute, a research establishment based in Scotland, explained, not all macroalgae have the same biostimulant qualities, and research labs like those at James Hutton are able to benchmark any particular seaweed to see how it could help crops to perform.

Also in the session, Martin Sutcliffe, Aquaculture Innovation Lead with the UK Agri-Tech Centre, gave examples of how the uses of seaweed in agriculture are being explored. He warned, however, that the industry has some issues, including high overheads, a high price per tonne (compared with some other animal feeds), currently low biomass volumes and the seasonality of seaweed harvesting.

Kyla Orr

Dr Kyla Orr of KelpCrofters, which is involved in seaweed farming and processing, said that biostimulants are a good product to aim at. There is already an established market, with 40% of biostimulants already seaweed-based, and these products fetch a decent price.

As she pointed out, kelp can be used for biostimulants without drying, which is a huge benefit to seaweed farmers, and the whole kelp plant can be used, minimising waste.

There are challenges too, however, not least stiff competition and the requirement to test and gather verified data to show that the product does what is claimed.

KelpCrofters has been developing “wet processing” techniques to manufacture biostimulants and related products, involving techniques such as fermentation, ensiling and cold-pressing.

Seaweed works – Dr Orr cited a study her company had been involved with using biostimulants to support spring barley crops in Scotland. Kelp and Alaria extracts increased yield by an average of between 4% and 8%.

Finally, Dr Maria Hayes, a Senior Scientific Officer at the Teagasc Food Research Centre in Dublin, gave an overview of the Irish seaweed sector. At 29,500 tonnes, Ascophyllum nodosum (“Asco”) is Ireland’s largest seaweed crop by far. Asco is almost exclusively wild-harvested rather than farmed and represents serious competition for seaweed farmers.

Farmers looking to tap into this market need to be aware of the high capital expenditure costs, she said, and they need to be very clear about which products and which markets they are aiming at.

The panel discussion covered more questions on the challenges and pitfalls of this market. Dr Orr noted: “Farmers want to know what your product will do for their crop. It is a long journey, and you have to commit to what it is that you want your biostimulants to deliver.”

Lessons from other sectors

In the second session, attendees heard from a range of speakers about what the seaweed sector could learn from others in the marine economy.

Dr Iain Berrill, Head of Technical with Salmon Scotland, explained how important provenance is to Scotland’s salmon producers. While Scotland ranks third in the world by production volume, he said, it cannot compete on volume price with Norway and Chile , so it has to focus on quality. And, as he stressed: “We are not afraid to use our Scottishness.”

Steven Flanagan

Steven Flanagan, a strategic communications expert with Weber Shandwick, said that in common with other industries, seaweed producers need to be aware of the need for “social licence”, especially if a new development is being planned. As he put it: “How do you tackle a lack of understanding if it is combined with scepticism?”

He advised starting by understanding the local community to get a feel for what their issues are and who your potential allies might be. In too many cases, he said, developers have ignored this at their peril.

Amanda Brown, of Scotland Food and Drink, shared the results of a survey of Scottish consumers that showed that provenance was seen as important, particularly when it is seen as supporting the local economy and demonstrating quality.

Finally, Alison Muirhead, of the Soil Association, set out the opportunities and challenges for seaweed producers looking to certify their product as organic.

Added value from seaweed

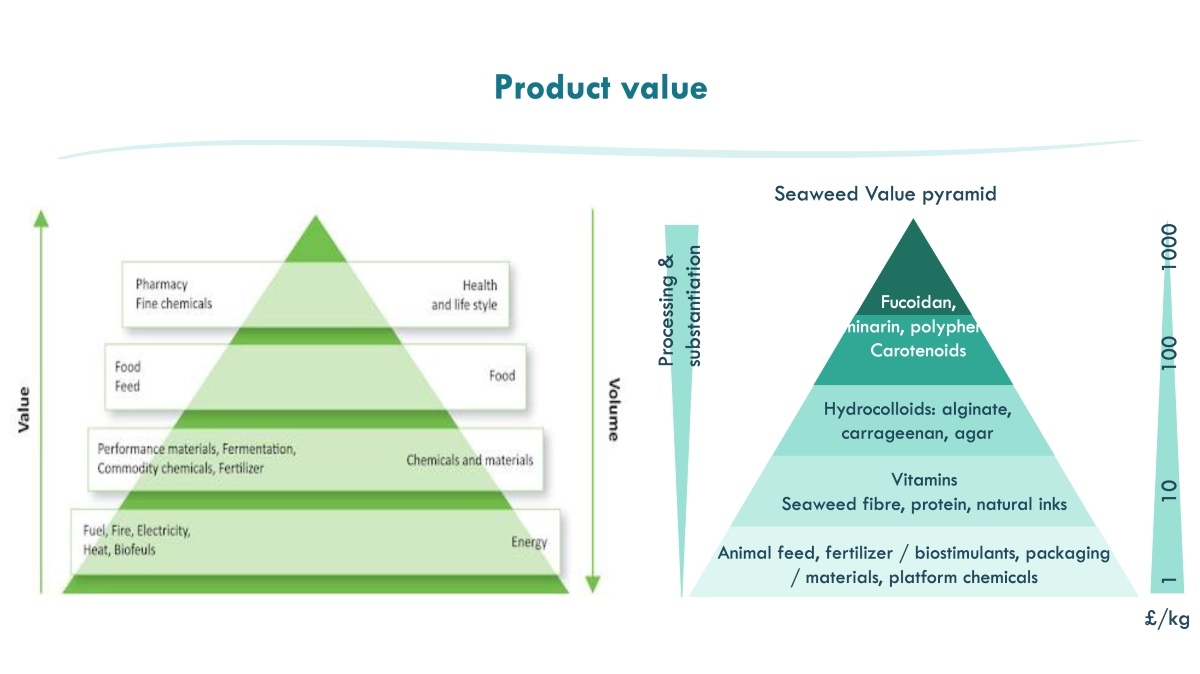

Growing seaweed is only one part of the challenge. Turning it into a saleable product – and even turning it into a product that can be stored and transported without rapidly deteriorating – requires processing.

In the third section, Dr Charlie Bavington, founder of biorefinery business Oceanium, explained the seaweed “value pyramid” (see graphic). Seaweed is an expensive commodity compared to many terrestrial crops, so it makes sense to focus on the higher value products that can be derived from it rather than lower value applications such as fertiliser and biofuel.

There are polysaccharides, he said for example, that are unique to seaweed species. For all high value extracts, he stressed, purity and proven bioactivity are important. And he stressed, while the environmental benefits of growing seaweed are a factor, it is the benefits of the product itself that count most.

Charlie Bavington

Environmental benefits are also not yet fully evaluated, Bavington argued. He warned: “We need to justify the claims we’re making about the social and environmental benefits of seaweed.”

Dr Emily Kostas, a UKRI Future Leaders Fellow and Lecturer in Sustainable Biorefining and Bioprocessing in the Department of Biochemical Engineering, University College London, explained the different thermochemical technologies used to process seaweed at low, medium and high temperatures, and the different products that these processes are suitable for.

Attendees also heard a talk from Dr Rhiannon Rees, CEO of PlantSea, a start-up business that uses seaweed-based biopolymers to create alternatives to conventional plastic. Its main product is an alternative capsule laundry liquid to replace the soluble plastics currently used.

Dr Jessica Adams of Aberystwyth University reported on a pilot-scale biorefinery set up to explore how biorefining could work at a commercial scale. She said some valuable lessons had been learned, including:

• Substrate quality matters. Holdfasts full of shells or small stones will rapidly blunt macerators.

• Choose equipment materials carefully. At lab level glass is preferable, but at a larger scale stainless steel is more robust.

• Be aware of acid and element reactions. For example, if using steel, be aware that hydrochloric acid is highly corrosive. The Aberystwyth project used sulphuric acid instead.

• Understand process bottlenecks. Dr Adams said: “We used a 50-litre reactor for one step, the biggest we had, and we sometimes had to use it two or three times a day. When we replaced it with a 500-litre reactor, it took a half a day off the process.”

And Dr Julie Maguire of Bantry Marine Research Station in Ireland – the largest supplier of seeded string in that country – described the bottlenecks and opportunities facing the seaweed aquaculture sector. She stressed that there is fierce competition from seaweed farmers in Asia and, closer to home, businesses harvesting wild seaweed.

Drying and processing are expensive and seaweed products can be hard to market – which is why collaboration is important. Licensing regulations can also be complex.

The opportunities are also there, however, and Dr Maguire pointed to the fact that European demand for seaweed is growing at around 7-10% annually. She stressed that business customers are not going to pay more for a seaweed-based alternative, so it is important to focus on the things that terrestrial crops cannot offer.

The panel discussion considered what needs to happen for the industry to take off. As Charlie Bavington put it: “We need to join up the value chain and every part has to work together.”

Jon Burton, Thai Union

Jon Burton, Thai Union

Markets and buyers

The final session of day one addressed the question of who is buying seaweed and why? Unilever’s Sarah Hosking has the job title of Biosourcing Manager, which effectively makes her a talent scout for novel materials.

As she explained, Unilever is interested in a wide range of applications, from antimicrobials and emulsifiers to flavourings, renewable packing and skincare products.

Jon Burton is Director for the Alternative Protein business unit at Thai Union, the global seafood group. He said that Thai Union’s strategy “From seafood to marine nutrition” meant that the business is interested in macroalgae both as a base product and as an ingredient, with brands such as John West’s “Plant Power” line of products.

Sarah Hosking

Christine Maggs, a Non-Executive Director of Ocean Harvest Technology – and Queen’s University, Belfast – explained seaweed’s role in the animal and aquafeed market. She said that studies have shown that including seaweed in feed not only improves growth, yields and product quality but also animal welfare.

Finally Alan O’Sullivan of biorefiner BeoBio and Callum O’Connor of seaweed-based alternative plastics business Notpla described how seaweed is used by their respective companies.

Walter Speirs

Lessons from a decade of the SSIA

Walter Speirs was one of the key figures who set up the SSIA in 2014. He was one of the first farmed mussel producers in Scotland, and is also a director of the Mussel Inn seafood restaurant, which he set up in 1998, and a co-founder of the cooperative, the Scottish Shellfish Marketing Group.

As keynote speaker on the second day, looking back at what the SSIA has achieved and ahead to what comes next, he said: “I want to be positive, but I want to be honest as well.”

For the cultivated seaweed sector, he said, the big question is “where is the financial return coming from?”

Seaweed is never going to replace cabbage, he conceded, but he said the Scottish industry could learn from the New Zealand greenshell – or green-lipped – mussel industry, which reinvented its product as a superfood and nutritional supplement for people and their pets.

Policy changes, such as the introduction of nitrogen or methane credits (along the lines of carbon credits) or a tax on single-use plastics, could make seaweed-based alternatives more affordable. Planning and water quality are also issues the sector could be campaigning on, he said.

He advocated working together with the seaweed industries elsewhere in the UK – although he did not recommend setting up a UK-wide body – and he said more broadly that collaboration within the industry is key.

From his experience with the SSMG he stressed that success is based on human relationships: “Co-ops are about people – if the people don’t work together, a co-op doesn’t work.”

Gordon McDougall leads the biostimulant workshop

The morning of day two concluded with two parallel workshops, on biorefineries (led by Dr Emily Kostas) and biostimulants (led by Dr Gordon McDougall).

The conference finished with a discussion on scaling and future prospects. Dr Kati Michalak of SAMS, the Scottish Association for Marine Science, summarised the results of a major international study known as ASTRAL (the All-Atlantic Ocean Sustainable Profitable and Sustainable Aquaculture project).

As part of ASTRAL, SAMS monitored the growth of seaweed crops and their quality when planted at different times of year and at different depths. One of the things learned, she said, was that it is better to change the depth at which seaweed is growing at different times of the year.

Jenny Readman, of CPI (the Centre for Process Innovation). explained the steps that must be taken when assessing, developing and finally setting up a process, from concept to commercial reality.

Dr Sophie Corrigan, of the Natural History Museum, explained the importance of maintaining healthy wild stocks of seaweed, not least as a biodiverse source of future seed. Overharvesting in the past had had devastating effects, she said.

Dr Frederick de Boever, of the FABRICS Project, talked about the project’s work with microbe-host interactions, and Dr Kelly Stewart, of IBIOC (the Industrial Biotechnology Innovation Centre), described how the ancient process of fermentation is being used with the latest science to develop new, cutting-edge products.

Most people walking along a seashore will have no idea just how much potential is locked up in seaweed – but unlocking it, it is clear, will take innovation, hard work and collaboration.

See Fish Farmer’s interview with Rhianna Rees at youtu.be/R07D7V0Z0QM