Shelling out for nature: shellfish farming and its ecosystem benefits

As more studies and papers emerge about the wider ecosystem benefits of farming low trophic aquaculture species, there is increasing interest in how companies might benefit financially from them, in addition to selling the nutritious food they produce.

Oyster, mussel and seaweed farming are the main areas of interest and the tangible benefits they provide include the provision of refuge, habitat, nursery areas and food for many other marine creatures. I looked in detail, for example, at the Ropes to Reefs project in the February issue of Fish Farmer.

However, it is the ecosystem services provided by these farms, including sequestration of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous, that are of particular interest to the aquaculture community.

Several UK and European companies already include payments for ecosystem services as part of their business plan but, as yet, there appears to be no official trading platform for marine-derived nature credits and no metric for defining them.

Globally, there are many examples of both voluntary and traded environmental and ecosystem markets, along with systems to allow payments for ecosystem services, but these all relate to land-based agriculture or arboriculture.

The exception is a voluntary blue carbon credit issued by the Japan Blue Economy Association (JBE) to Urchinomics in 2020 to restore kelp forests in Japan. Urchinomics was the first company to achieve this.

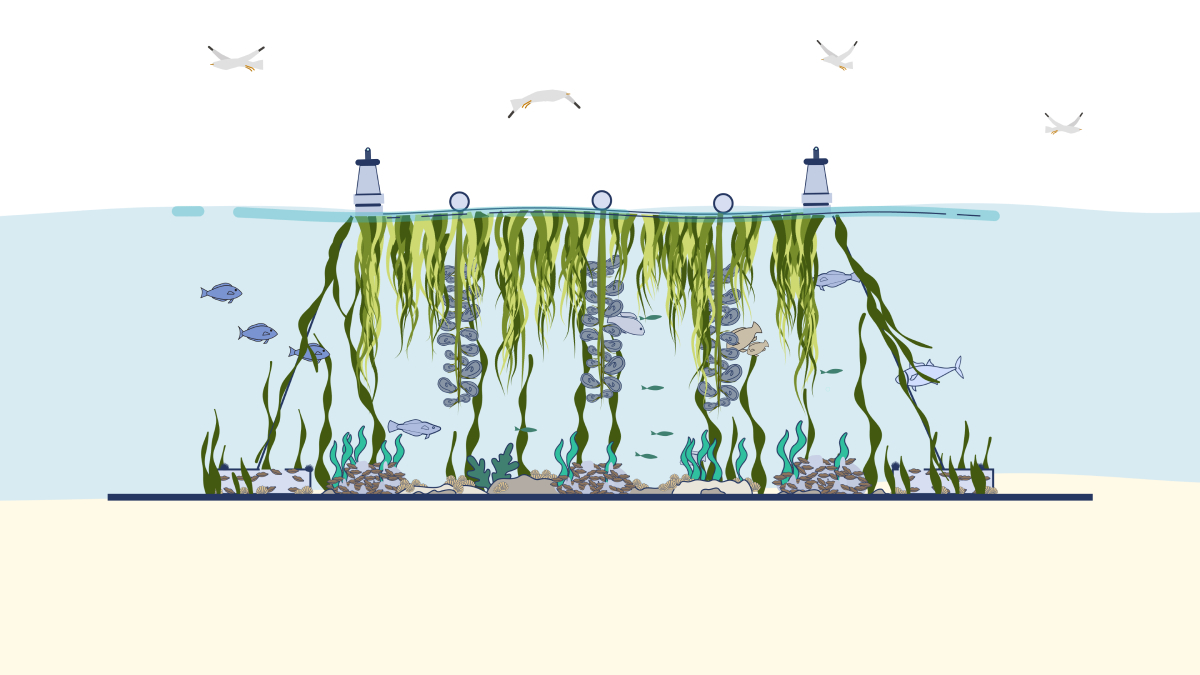

In the UK, Algapelago, co-founded by cousins Olly Hicks and Humphrey Atkinson, who is also a product manager at Notpla, is currently fundraising to set up a Blue Forest Programme, which aims to revive and regenerate 11 acres of degraded coastline off the north Devon coast. Collaborating with marine researchers, the company has already initiated research to demonstrate how seaweed and shellfish cultivation can contribute to ocean restoration.

The project will plant oyster reefs on the seabed, grow mussels in the midwater and kelp at the surface, and will develop a Blue Forest template that Hicks hopes could be used to kick-start ocean regeneration on a global scale.

An important part of the model is to quantify the biodiversity benefits such a system can provide and to develop the metrics necessary to open up a nature credits market.

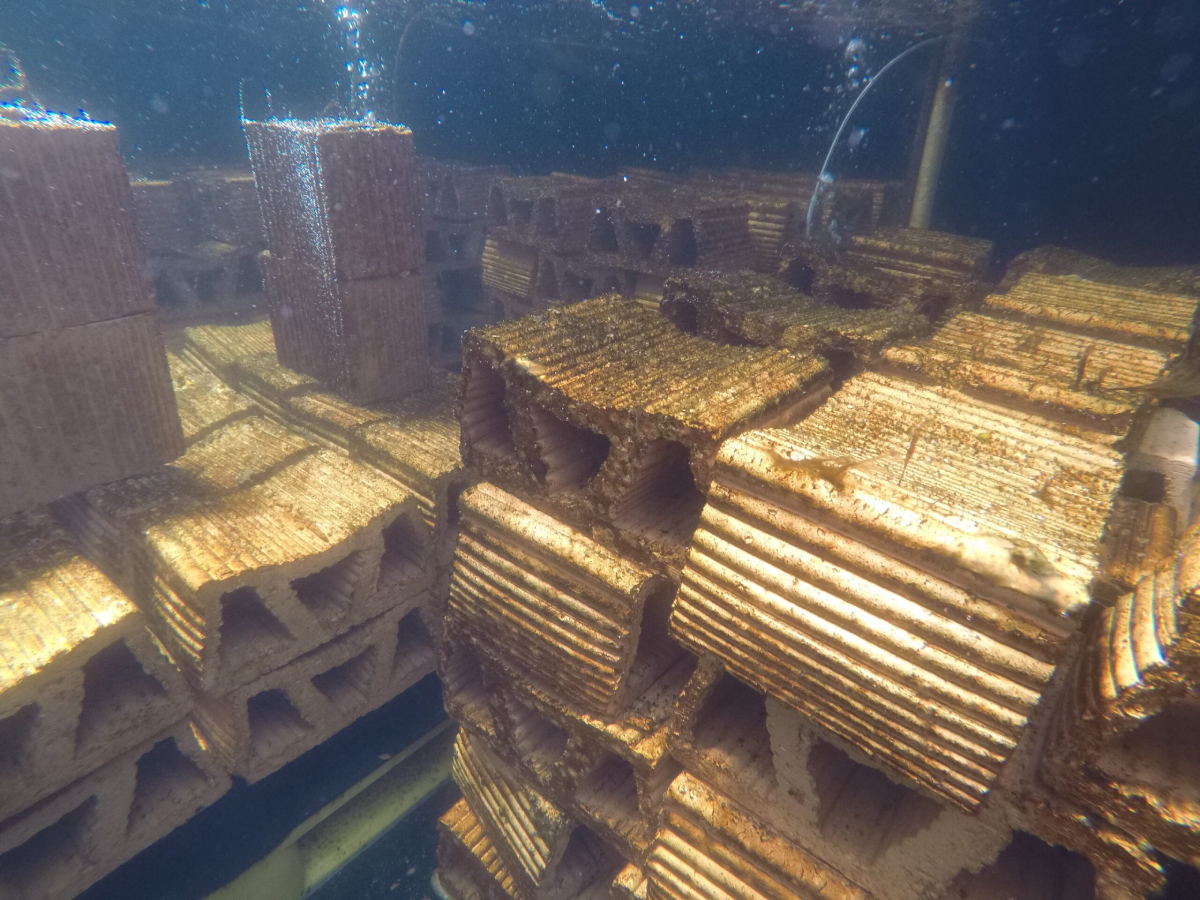

Oyster Heaven, based in the Netherlands, is an oyster restoration company with a mission to regenerate oyster reefs at scale, using a “Mother Reef” comprised of small biodegradable bricks, on which juvenile oysters are settled. By 2027, it aims to have planted more than 100 million oysters.

The company has calculated that a four million oyster reef would remove 2.5 tonnes of nitrogen per year and sequester between 100 and 900 tonnes of carbon, as well as protecting the coast from tidal surges and increase local biodiversity.

The need to attract philanthropic or academic funding to set up projects has long hampered the progress of oyster restoration projects and Oyster Heaven’s model is to sell biodiversity credits to other companies to make marine regeneration financially sustainable.

Founder and Business Lead George Birch believes that investments in nature should be treated as core operational costs necessary for a company’s survival, risk management and profitability. In other words, as an essential cost of doing business.

He explained that CSR initiatives typically allocate a small portion of profits to projects that benefit the community or the environment and generate good publicity as a result.

Birch argues that if a company contributed say 1% of profits to a nature-based investment to help maintain the ecosystems that support their supply chains and operations, it would unlock more investment to restore nature, whilst enhancing their competitive position and long-term profitability.

This is important, because a 2023 analysis by PwC found that 55% of global GDP, equivalent to an estimated $58 trillion (£46 trillion) is moderately or highly dependent on nature.

The ability of shellfish to remove nutrients is vital in nutrient-rich areas such as coastal zones and estuaries, where high levels of nutrients can lead to eutrophication, with subsequent knock-on effects such as a greater proliferation of algal blooms.

Soaking up nitrogen

Seafish, along with the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), supported by Longline Environment Ltd and the Fishmonger’s Company, undertook a major study to look at the capacity of the UK bivalve sector to remove nitrogen and to quantify the potential financial savings that would result.

The study used elemental analysis to measure the nitrogen and carbon content of blue mussels, Pacific oysters, native oysters, and Manila clams. The tissue and shell of each species has a different elemental composition and different farming methods also affect nitrogen content.

Longline Environment’s Farm Aquaculture Resource Management (FARM) model, which combines information on different shellfish species, their environment and farming practices, was used to estimate how many bivalves could be harvested and how much nitrogen they could remove from the water.

The information was used with national bivalve production data from 2019 to provide the results. These showed that the UK bivalve industry removed between 126 and 362 tonnes of nitrogen in 2019. Blue mussels were the main contributors, removing more than 92% of the total nitrogen removed by shellfish.

Scotland and England were the top regions for nitrogen removal, reflecting the high production of bivalves in these areas.

A comparison was also made of the amount of nitrogen removed by bivalves with the amount of nitrogen entering UK waters. This showed that Northern Ireland and Wales removed the highest proportion of their nitrogen loads through bivalves, with averages of 0.25% and 0.24% respectively.

The report suggested that in England and Scotland, bivalve harvests could offset a significant portion of industrial nitrogen sources, resulting in tangible water quality improvements.

In terms of financial savings, a comparison with chemical and manual wastewater treatments and stormwater control showed that the total savings across the UK could be between £7m and £21m a year. And in areas at risk from eutrophication, bivalves could save an additional £1.1m to £3.2m per year, compared to the costs of effective catchment management.

The capacity for nitrogen removal is closely tied to the size of the industry and increasing future bivalve production will lead to even better nitrogen removal.

Research by the University of Portsmouth in the Solent found that native oysters have an annual value of £37.44m for nitrogen removal and £6.77m for phosphorus removal. They also estimated that reducing one tonne of nitrogen through alternative methods costs about £295,000. Applying this figure to the Seafish work suggests that using bivalves could lead to national savings ranging from £37m to £106m.

Similar studies around the world demonstrate similar results, with annual oyster nitrogen removal in Chesapeake Bay, for example, ranging from £439,920 to £9.82m. In Denmark, mussel farming in the Limford is estimated to provide savings of between £1.34m and £1.62m.

The take-home from this is that while bivalve shellfish and seaweed offer valuable ecosystem services, no-one has yet found the key to unlock the route to monetisation. When they do, I believe it will also make shellfish farming a more attractive proposal and pave the way for expansion of the industry.