Alaska at the crossroads

The proposal to relax the rules that currently bar any finfish farming in Alaska might seem limited, but it has already met with a backlash from the state’s catch fishery sector.

As reported in Fish Farmer’s March issue, Alaska’s Republican Governor, Mike Dunleavy, introduced draft legislation in February this year that would partially lift the state’s ban on finfish aquaculture.

So far, those representing the Alaskan fishing community are less than happy – even though Alaska’s iconic salmon fishery would arguably not be directly affected.

The Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association (BBRSDA), which represents more than 1,800 fishermen in the sockeye salmon fishery of Bristol Bay, Alaska, said: “Finfish farming directly contradicts BBRSDA’s mission to maximise the value of our fishery for Bristol Bay’s fishermen. Alaska’s wild salmon are the gold standard for quality and sustainability - allowing farmed fish in Alaska would compromise our industry and weaken the market for our fishermen.”

And writing in the Anchorage Daily News, Tim Bristol, Executive Director of not-for-profit organisation SalmonState, which advocates for wild salmon and wild salmon fisheries, said: “Not only does Gov Dunleavy’s fish farm bill amount to a giant ‘go to hell’ message to Alaska fishing families, it’s emblematic of his long-standing lack of stewardship of Alaska’s lands and waters. In his mind, clean water, intact habitat and carefully managed wild fisheries are obstacles to unfettered resource extraction.

“Attempting to bring fish farms to our wild state illustrates just how divorced Dunleavy is from the real Alaska.”

Currently, Alaskan law prohibits finfish farming except for private non-profit salmon hatcheries. The draft bill HB 111 (“Finfish Farms and Products”) would authorise the Commissioner of the Department of Fish and Game, in consultation with the Commissioner of the Department of Conservation, to permit the cultivation and sale of certain finfish in inland, closed system bodies of water.

The legislation:

• Requires all finfish acquired with a finfish farm permit to be sterilised triploids which are unable to reproduce

• Prohibits cultivating pink, chum, sockeye, coho, chinook and Atlantic salmon

• Requires finfish farms to be enclosed within a natural or artificial escape proof barrier

• Authorises stocking a lake on private property with finfish for personal consumption without a permit if the lake is enclosed with a natural or artificial escape-proof barrier.

The proposed legislation would continue to ban any form of open net pen farming at sea, and it would also not allow the raising of farmed salmon species – even in enclosed, land-based facilities.

If enacted, even the reforms would leave Alaska with one of the strictest regimes, as regards finfish farming, of any jurisdiction in North America.

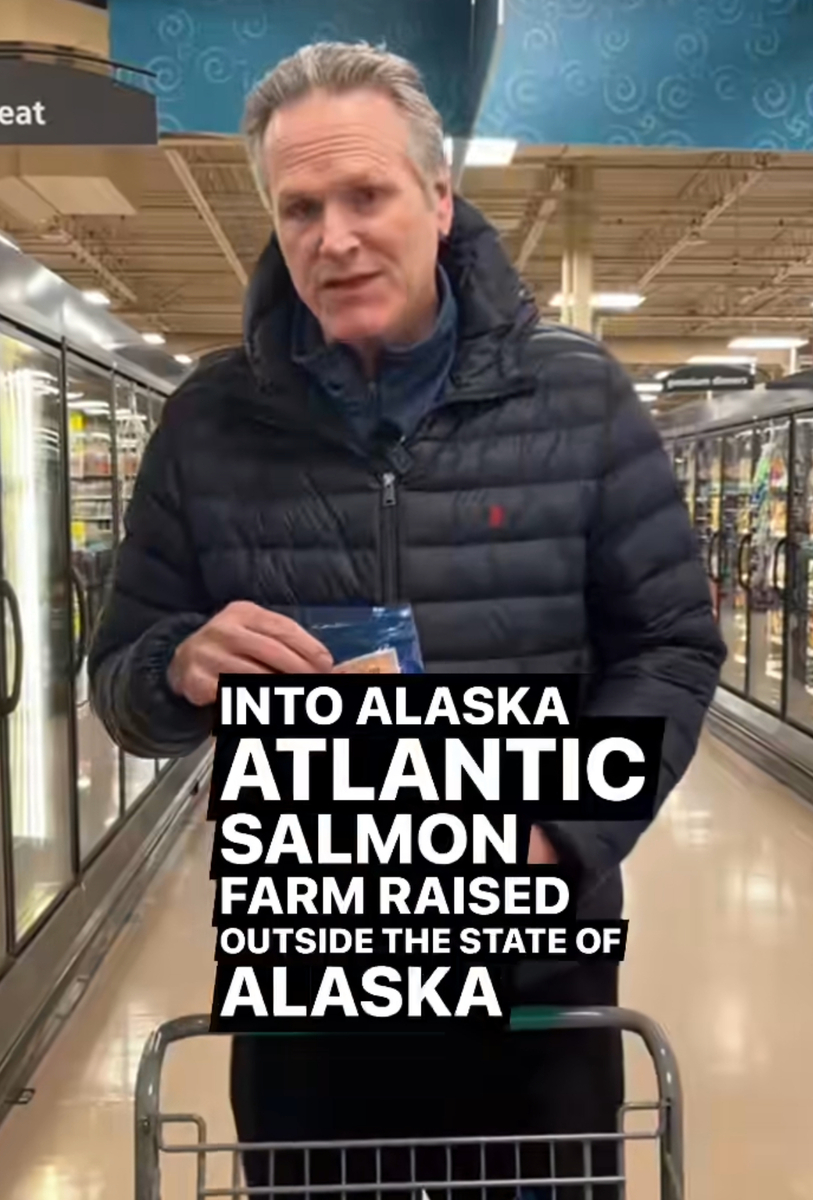

Governor Dunleavy recently posted a video on social media in which he lamented the number of farmed, imported varieties of seafood available on Alaskan supermarket shelves – which he said could be replaced by homegrown varieties of fish such as tilapia and catfish, both of which are farmed in a number of other US states.

The primary reasons for the prohibition of fish farming in Alaska include:

• Environmental concerns: There are fears that fish farming could lead to pollution, habitat destruction, and the spread of diseases to wild fish populations.

• Genetic risks: There is a risk that farmed fish could escape and interbreed with wild fish, potentially altering the genetic makeup of wild populations.

• Economic considerations: Alaska’s economy relies heavily on commercial fishing, and there are concerns that fish farming could undermine this industry.

Arguments in favour of legalisation include:

• Economic benefits: Legalising fish farming could create new jobs and stimulate economic growth in rural areas.

• Food security: Aquaculture could help ensure a stable and sustainable supply of seafood, reducing dependence on wild fisheries.

• Technological advances: Innovations in aquaculture technology can minimise environmental impacts, making fish farming a more sustainable practice.

The question of whether fish farming will ever be legal in Alaska remains open. It is a complex issue that requires careful consideration of environmental, economic and social factors. As technology advances and the global demand for seafood continues to rise, the state may be persuaded revisit its stance on aquaculture.

Until then, the preservation of Alaska’s wild fish populations and their habitats, on which a significant proportion of the state’s economy relies, remains a top priority.

Fish farming or fish ranching?

Given the fierce opposition to any form of fish farming on the part of the Alaskan salmon fishing sector, it might come as a surprise that the industry relies quite heavily on salmon hatcheries.

Michelle Morriss, with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, said: “In contrast to hatchery programmes in other areas, Alaska’s salmon fishery enhancement programme was not built to mitigate habitat losses associated with human projects.

“Alaska has healthy well-managed wild stocks and a robust and healthy hatchery programme that was designed to minimise wild stock interactions and enhance fisheries.

“Our hatchery programmes for commercial fisheries are stakeholder driven and overseen by fishermen who strongly support Alaska’s mandate to protect wild stocks while enjoying the economic opportunities derived from renewable resources that are well managed.”

The Department of Fish and Game estimates that, in 2023, hatchery production accounted for 81% of the commercial fisheries harvest in Prince William Sound, 39% in Kodiak, and 24% in Southeast Alaska.

Pink and chum salmon are the species most commonly raised in this way. Only local, native stocks are permitted for use and the fish are released into the wild as juveniles. Most of their growing is done at sea.

Supporters of the programme would say this is fish “ranching”, not “farming”.

Meanwhile, shellfish offers a less controversial form of aquaculture that is already well established in Alaska. The state’s pristine waters offer a unique environment for the farming of various shellfish, and the combination of cold, clean waters and nutrient-rich ecosystems contribute to the high quality and sustainability of shellfish farming in the region. In particular oysters, mussels and clams – including littleneck clams, butter clams and geoducks, a kind of large, burrowing clam – are widely farmed.

Seaweed – crop of the future?

The next big thing to come out of Alaska’s seas might not, however, be one that arrives on the end of a hook or in a net, and it might not even end up on a dinner plate…it’s seaweed!

Seaweed farming, particularly kelp farming, is a growing industry in Alaska, with the state’s cold, nutrient-rich waters proving ideal for cultivation, and farms are beginning to emerge, offering economic and environmental benefits.

Some of the largest kelp beds in the world are found in Alaska.

Different types of red, green, and black seaweed are also farmed and gathered in Alaska.

Marine algae has been used by Alaskans as a source of food and materials for centuries. Recently, the farming of seaweed has gained attention for its commercial, food security, and climate change mitigation possibilities. Alaska presents an ideal location for the seaweed farming industry, as it has the longest coastline in the United States and more than 500 species of seaweed.

Seaweed production does not require fertiliser, fresh water, or arable land. Alaska has cold, fertile waters, lively community waterfronts, and a skilled maritime workforce interested in pursuing mariculture (the cultivation of fish and marine life for food). As such, Alaska could be at the cutting edge of the growing seaweed farming industry in the United States.

Jennifer Angelo, of NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, advises that all aquaculture projects in Alaska are located within state waters and are subject to leasing and permitting requirements by the state of Alaska.

In addition, many projects require federal permitting that may trigger both Endangered Species Act and Essential Fish Habitat consultation requirements.

Angelo says: “NOAA Fisheries does not regulate aquaculture projects in state waters, but we are providing links and information to assist applicants with seeking approvals from federal and state agencies with regulatory jurisdiction.

“The Alaska Aquaculture Permitting portal [akaquaculturepermitting.org/] outlines the steps necessary to receive state and federal lease and permits to conduct commercial marine aquaculture activities in the state of Alaska.”

Back in 2021, Markos Scheer, CEO of organic kelp and oyster farmer Seagrove Kelp Co, told local news site Raven Radio: “This is the kind of industry [seaweed] that could be a really significant leg on the economic stool for coastal Alaskans because you can do it in so many different places and do it viably.

“You know if we get the industry to a size that it needs to be, it’s gonna be a pillar of the economy for the next 100 years.”