A Welsh opportunity

Can an emergent seaweed industry be the disruptor that triggers blue growth across a number of priority sectors for Wales? A recent report suggests that it can, if the right action is taken.

As things stand today, Wales has only one seaweed farming business, one licensed farm not yet operating and one small hatchery on Anglesey.

That could all change, however, according to a study that has highlighted what seaweed could mean for the Welsh economy. Project Madoc is a comprehensive 12-month feasibility study, funded by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). Its purpose was to assess the economic viability, environmental impact and social acceptability of developing a sustainable and competitive industry for Wales, based on the cultivation and downstream processing of selected species of native seaweed.

Project Madoc’s intro states: “Wales now stands again on the brink of a new era of opportunity originating from and beyond our remarkably diverse coastline… this catalytic project illuminates an opportunity to accelerate a shift to a new and regenerative industry based on the sustainable farming of selected, native species of seaweed.”

And goes on “Seaweed is among the most scalable of nature-based solutions.

“Alongside its economic advantages, it can offer tangible solutions to the challenges posed by climate change and provide a plethora of ecosystem services.

“To do these things, however, it has to be farmed and at scale.”

Project Madoc (named after a legendary seafaring Welsh prince) was led, edited and managed by The Seaweed Alliance, a not-for-profit body, with input from selected independent experts.

The Seaweed Alliance co-founders Charles Blair and Fiona Trappe both came into the seaweed industry in 2017, from a background in regional development and regeneration.

As Trappe explained, their interest developed after seeing an example of seaweed cultivation in Tasmania (where Blair was living): “We were looking for untapped opportunities in the UK.”

The report warns that Wales is lagging behind countries that have done more to embrace this opportunity, including Norway, the Netherlands, Ireland, Australia and Scotland.

It says: “The highest ambition scenario indicates that Wales has the potential to build a £105m industry, contributing £76.3m to GVA (gross value added) and close to 1,000 jobs by 2033. This does not include the associated supply/value-chain or potential monetary value of ecosystem services derived from seaweed cultivation and resultant replacement of carbon intensive products. Viewed in the round, this equates to Wales generating £29.4m in salaries and remuneration, £81m revenue, with a profit of 27%”.

Charles Blair said: “The desire is there, but what’s needed is investment. It’s not just about primary production, it’s how it feeds into life sciences, biotechnology and so on. We need to turbocharge seaweed to elevate it from the peripheral into the mainstream as a driver of socio-economic growth for the wider Welsh economy in the context of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act, 2015.”

As an integral part of diligence research, the authors commissioned a comparative analysis specifically with Norway, The Netherlands and Japan as case studies.

Blair explained: “This went a lot deeper than relying on secondary sources. We wanted to know - and to convey to stakeholders - what Wales could learn from those cases and transfer and adapt for Wales to accelerate the establishment and growth of an industry in Wales; but much applies to the UK more broadly.”

The Netherlands has already started to explore the possibilities of seaweed farming, but, as Trappe and Blair are keen to point out, Wales has five times the coastline of the Netherlands and Belgium combined with a far wider range of coastal conditions and biodiversity. They pointedly question if we’re making optimum use of our natural (marine) capital. And, if not…why not? And how we change that?

Facilities and the technology for processing and biorefining will be key. Trappe and Blair stress that some investment by the state will be required to get the industry going, although it should not require subsidies indefinitely. Given this represents the emergence of an “infant industry” for Wales (as for most of the UK), some form of pump-priming intervention is not an outlandish proposition.

Native species with potential

The report recommends a focus on key native species - Palmaria palmata (dulse), Ulva lactuca (sea lettuce), Saccharina latissima (sugar kelp/kombu) or Alaria esculenta (winged kelp/Atlantic wakame). Specialising in this way would bring economies of scale benefits and accelerate innovation activities through simplification, the report says. The volume biomass that could be produced equates to 17,700 tonnes per annum by 2033.

Project Madoc also recommends a phased growth approach – a “beachhead strategy” – focussing resources initially on a small market area to create a stronghold for the future and enable seaweed farmers, industry processors, entrepreneurs, investors, and researchers to coalesce.

As well as biomass production, investment would also have to be directed to bioprocessing. All of which – across the entire seaweed industry supply/value-chain – presents Wales with opportunities for innovation, inward investment, technology and knowledge transfer resulting in quality, sustainable employment building resilience for coastal communities.

The report says the findings of the environmental assessment conclude that, in the Welsh context, there would be minimal negative environmental impacts: “Overall, the potential environmental risks of seaweed farming would be outweighed by the benefits, including water quality improvements, enhanced biodiversity, bioremediation, and coastal protection.”

The key recommended next step is to develop a comprehensive Seaweed Industry Development Plan for Wales, in three phases:

• Promoting and supporting capacity-building and knowledge transfer, focusing on three native species – kelp, dulse and Ulva.

• Creating industry demand to lead to scaling of farms and bioprocessing facilities to meet the needs of a seaweed bio-based sector.

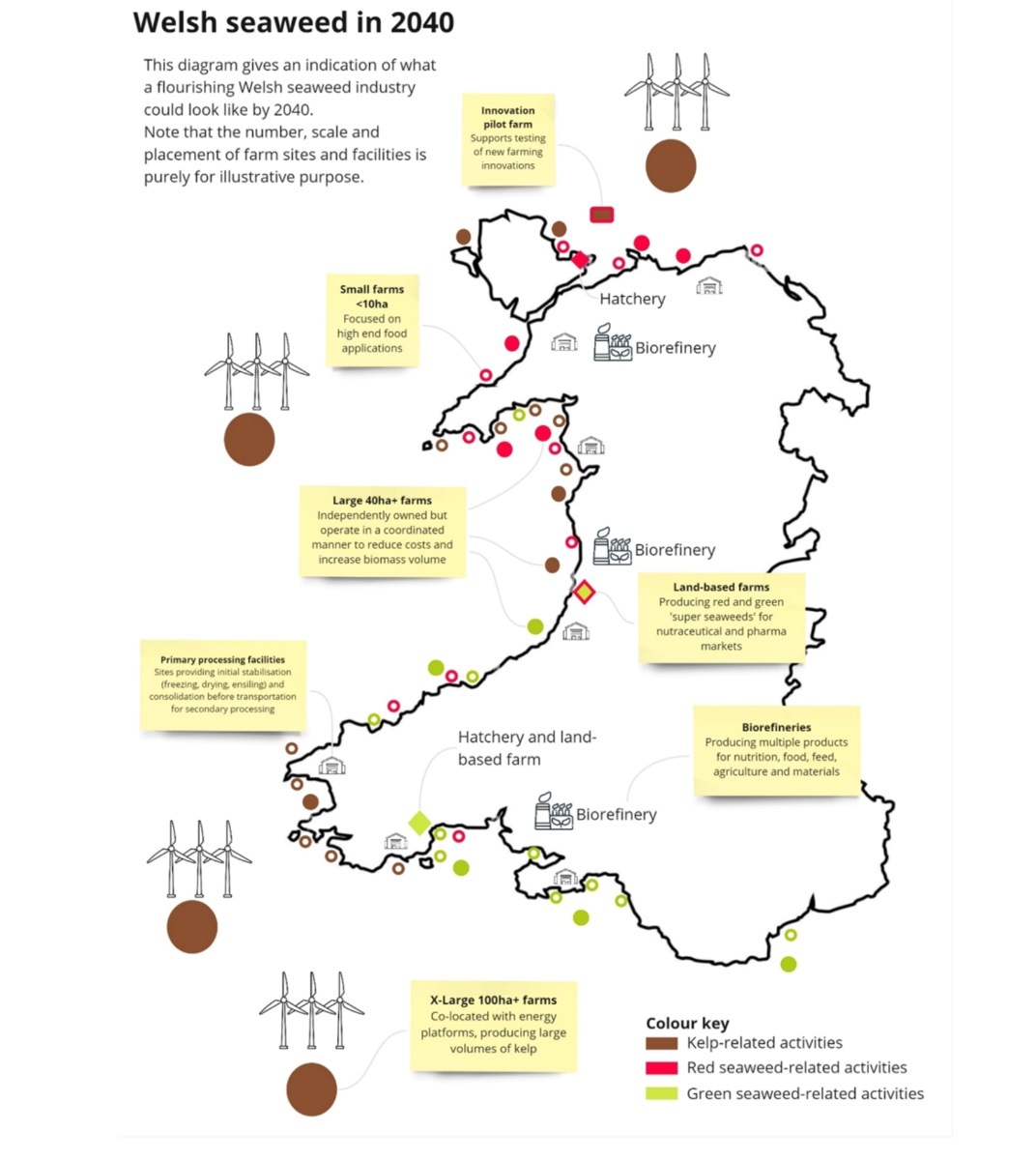

• Co-location with offshore wind farms.

Madoc’s market analysis concludes that “agri-food” applications have the best potential to kick-start a seaweed industry in Wales (this includes food, food additives, biostimulants and feed) as there is already an established food and drink industry. This aligns with and lends voice to Welsh Government policy and strategies for what is predominantly a rural economy.

The report sets out a three-phase approach:

Phase 1: Initially deploy clusters of small-scale farms working as a cooperative, supplying the agri-food sector, ie, artisanal food producers and restaurants regionally. This will promote and support capacity building, knowledge and skill transfer as demand grows.

Phase 2: Increase scale of biomass production capacity by grouping into larger farms, sharing infrastructure, thus enabling economies of scale. Supplying mainstream food manufacturing and other high-volume applications such as feed and bio-stimulants for the agricultural and life sciences sectors. In parallel, consideration also needs to be given to harvesting seaweed from the wild to fulfil any shortfall in demand.

Phase 3: From 2030 onwards, extra-large scale, offshore seaweed farms, co-located with offshore wind farms, will begin to enter the water, thereby providing high volumes of relatively low-cost biomass for biorefining and opportunities within the “bio-based alternative markets” such as packaging, chemicals and biofuels.

The report acknowledges importance of support on the part of local communities (coastal especially, where the majority of the Welsh population live and includes Welsh-speaking areas), and the need to address environmental and other concerns. It points out that seaweed farms could be sited in areas with currently high levels of unemployment, providing opportunities for local jobs.

The report’s environmental assessment concludes that the environmental impact of seaweed farms could be mitigated by careful selection of farm sites, and points out that seaweed production also comes with a number of environmental benefits, such as improved oxygenation and de-acidification of water, and increased biodiversity. Farms could also help reduce coastal erosion by absorbing wave energy.

SW industry graphic TSA “Model for a seaweed industry”

Where to start?

The report suggests that, in theory, almost 50% of the Welsh marine area is suitable for cultivating kelp. This equates to a total area of just over 1.5 million hectares – 106,000ha scored optimally – with a further 1,435,300ha considered suitable.

An analysis proposes five development sites for the first phase of seaweed production: Llandudno, South Wales; Puffin Island, off Ynys Mon (Anglesey); Holyhead, Ynys Mon; Fishguard, south-west Wales; and Swansea, South Wales. In addition, Rhyl Flats Wind Farm could serve as a potential example for a co-location pilots.

The report argues: “The well-established ecosystem services offered by seaweed can form the basis of a sustainable, regenerative industry for Wales, with an array of high-value, commercial applications. It can feed the supply and value chains of a rapidly advancing Welsh bioeconomy, while at the same time replacing seaweed feedstock imported from East Asia…an evolving Welsh seaweed industry can form an intrinsic component of a wider new, blue economy for Wales, learning and adapting from excellent models in Europe and Australia to accelerate the agenda.”

And the authors conclude: “With the necessary levels of ambition, commitment and investment, a competitive Welsh seaweed industry is eminently technically and commercially feasible, and socially and environmentally desirable.”

Trappe and Blair acknowledge the diligent input by the report’s key contributors and for the many insights provided by a vast array of stakeholders and interviewees in the UK and internationally.

“But we have to now take this up the gears if Project Madoc is to prove impactful as a disruptor for blue growth,” they reflected.

The Seaweed Alliance stands ready to collaborate with interested parties in government, industry, academia and investors to lead that charge.