A turnaround in salmon survival?

After two tough years, reports Sandy Neil, salmon mortalities are back to something like normal.

Survival rates for farmed salmon plunged deeply over the last few years, but now seem to be rising back up.

Why? Is this turnaround down to the industry learning, or just a cooler, wetter summer? And is it likely to keep rising?

“There’s no doubt 2022 and 2023 brought challenges linked directly to environmental conditions and that fish died as a result,” explains Scottish Sea Farms’ Head of Veterinary Services, Ronnie Soutar. “The sea was significantly warmer, particularly last year, and although the temperature was well within the comfortable range for salmon to thrive, it was also ideal for dangerous planktonic organisms, jellyfish in particular, with resultant harm to fish.”

Further explanation was given by Dr Darren Green, Senior Lecturer in Aquatic Health Modelling at the University of Stirling’s Institute of Aquaculture.

“Typically for fish, salmon rely on high reproduction rates to ensure their next generation, rather than high survival rates found in mammals,” Dr Green says.

“Pests and diseases challenge them, including bacteria and viruses, sea lice, algal blooms, and in recent years, growing problems around gill health and microscopic jellyfish swarms.

“Salmon prefer cooler temperatures, but unfortunately not all their pests do. Hot summers and warm winters increase stress and disease risk. Global warming contributes, and 2022-4 had the warmest sea-surface temperatures on record in the north Atlantic. This likely exacerbated higher autumn mortality rates across these years, despite advances in farming technology.”

Signs of a turnaround came in August 2024, when Mowi Scotland recorded its “lowest monthly mortality for over eight years and achieved record high feeding and growth rates in the cooler coastal waters.”

Ben Hadfield, COO of Mowi’s operations in Scotland, Ireland, Faroes and Canada East, explained at the time: “The decline of El Niño conditions, much cooler summer air temperatures and higher rainfall have all benefited our salmon farming operations.

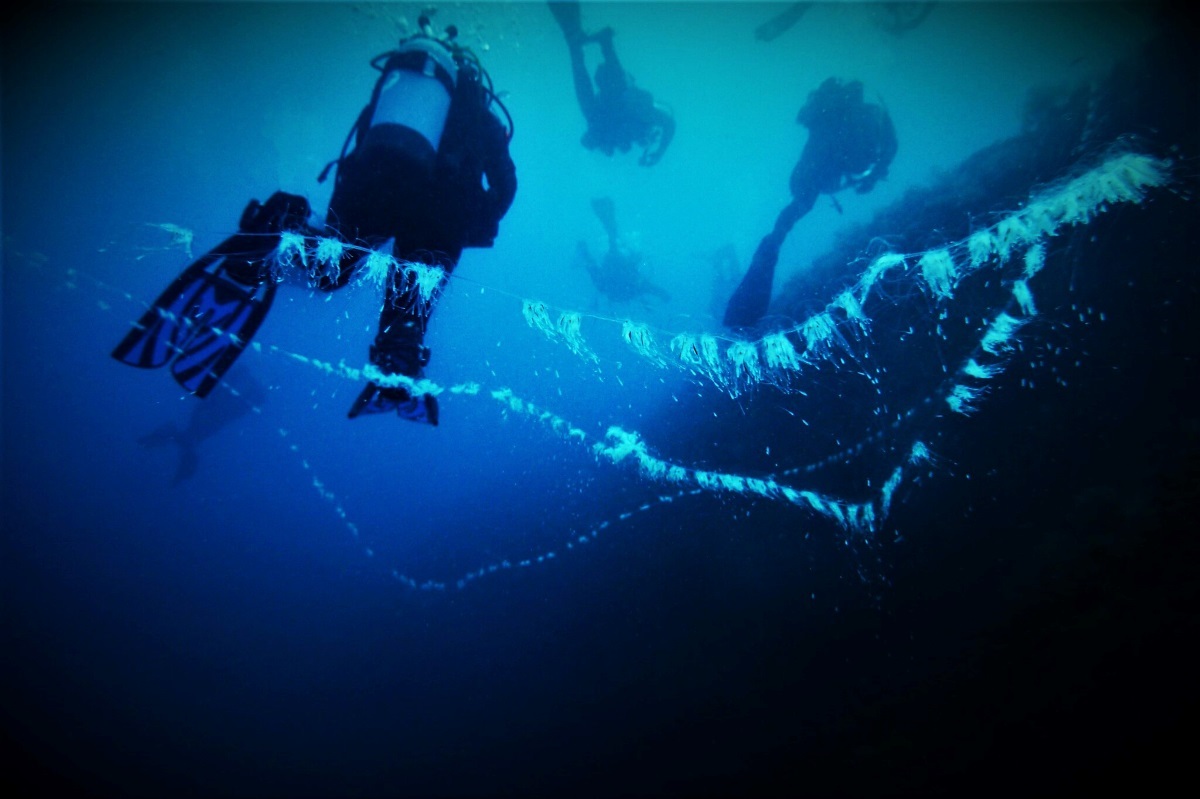

“This weather, combined with our enhanced mitigation measures such as the high capacity to treat salmon with freshwater and the use of bubble curtains to prevent micro jellyfish and algae entering our farming systems, have so far proved effective.”

But farmers should not be complacent, added Mowi Scotland’s Production Director Sean Anderson.

He warned: “The threat posed by jellyfish and algae has not gone away, and may well challenge us in September.”

A few weeks later industry body Salmon Scotland celebrated a 98.18% survival rate on farms in September, traditionally the most challenging month for salmon in the sea.

Salmon Scotland said: “The percentage of fallen stock was around half the rate recorded in September last year, when warm sea temperatures in the autumn led to micro jellyfish blooms which can harm fish.

Throughout 2024, survival rates have been consistently high, reaching 99.03% in June.”

Cooler seas – for now

Which way is the trend in farmed salmon health and welfare going?

“This year the temperature and other environmental parameters have been much more in line with longer term averages and there have been fewer associated challenges,” says Ronnie Soutar.

“That doesn’t mean, though, that 2024’s much improved health and welfare parameters, not only survival rates, have been down to good luck.

“We have, for example, still seen harmful jellyfish species, including apolemia, impacting on farms in 2024 and AGD [amoebic gill disease] has been a challenge in the later part of the year.

“However, the lessons learned from the recent difficult years, on top of the long-term investments and innovations that the sector has implemented, have really shown to be effective in countering these issues.

“As with routine checks on sea lice and AGD, the level of monitoring of potentially-harmful marine organisms is far greater than it’s ever been. The mitigation measures are now well-rehearsed and are put into action quickly and effectively. We now have a better range of fish health and welfare protection options than at any time in my (now very long) career.

“We may face challenging conditions in future years, possibly in ways that are hard to predict, but I have no doubt that the Scottish salmon sector as a whole is better prepared than ever to rise to these challenges.”

Salmon Scotland pointed to the industry’s investment delivering the “best survival rate for four years”.

Dr Iain Berrill, Head of Technical at Salmon Scotland, says: “Investment of nearly £1bn since 2018 on fish health and welfare measures has helped deliver these outstanding survival rates.

“This includes freshwater treatment vessels, investment in research, a reduction in the time that farm-raised salmon spend at sea, as well as staff training and improved monitoring systems to help farmers respond to natural challenges that come with warming seawater.

“Increasing the number of vessels that farmers have access to improves response times and flexibility.

Understanding more about the challenges we faced in the last two years has helped farmers make targeted investments in the things that help them to keep their fish alive and healthy.

“As we continue to innovate, offshore and semi-closed containment for the marine phase could help to separate salmon from naturally occurring organisms, while there is also broodstock development taking place to breed more climate-resilient salmon and larger smolts that spend less time at sea.”

Premature celebration?

But a note of caution was struck by the wild salmon conservation charity WildFish. “This celebration of comparatively lower mortality rates in August and September is undoubtedly premature,” says its Director, Scotland, Rachel Mulrenan.

“The trend towards higher mortality has accelerated in recent years, but it is not new; monthly mortality rates began to increase as early as 2010, roughly when amoebic gill disease became established in Scottish salmon farms.

“Globally, large-scale mortality events on open-net salmon farms are happening more frequently, and at greater scale, than ever before – due to climate change but also increased reliance on technology.

“Regardless of lower water temperatures this summer, there were 126 reports to the fish health inspectorate between August and mid-October this year, indicating mortality incidents of >1% of stock.

“It’s also notable that 41% of Scottish salmon farms were fallow or empty in August and September this year, reflective of an industry trend to harvest early to avoid fish being exposed to the warmest months. This is having knock-on effects with regard to jobs.

“What we are seeing is the result of a fundamentally unbalanced and unsustainable food production system, with existing problems exacerbated by warming waters. Sea lice parasites proliferate on salmon farms, due to the large number of ‘hosts’ in the cages; this proliferation is faster in warmer waters.

“Rising resistance to chemical treatments for sea lice has necessitated the introduction of physical treatments, as well as the unethical use of cleaner fish (many of which also die).

“Alternative treatments, such as thermolicers and hydrolicers, and the associated crowding, can be fatal for salmon whose gills have been compromised by disease or micro-jellyfish; both of which are facilitated by higher water temperatures. Alternative treatments can also cause mass mortality incidents directly.”

The Scottish Government was also cautious. “It is too early to draw any firm conclusions from the data available at this point,” a spokesperson says.

Looking ahead, Dr Darren Green at the Institute of Aquaculture says: “Industry reports this month that autumn mortalities are their lowest for four years, and by October the seasonal peak in health challenge is passing.

“Recent innovations may have mitigated disease threats, however long term, new diseases emerge to challenge farmers. The tepid summer may also have helped, and La Niña climate conditions suggest some cooler weather coming medium term, but global warming is with us to stay.”