Scaling up

Bacteria are being put to work, extracting the useful elements from harvested seaweed, as Robert Outram reports

We’re in the John Coulson Building at Edinburgh’s Heriot-Watt University, watching macerated sugar kelp spinning furiously in what looks like a sophisticated food processor.

The aim of the exercise is not, however, to create a nutritious seaweed smoothie. It is part of a trial involving fermentation to unlock value from the algae species that grow abundantly along Scotland’s coastline.

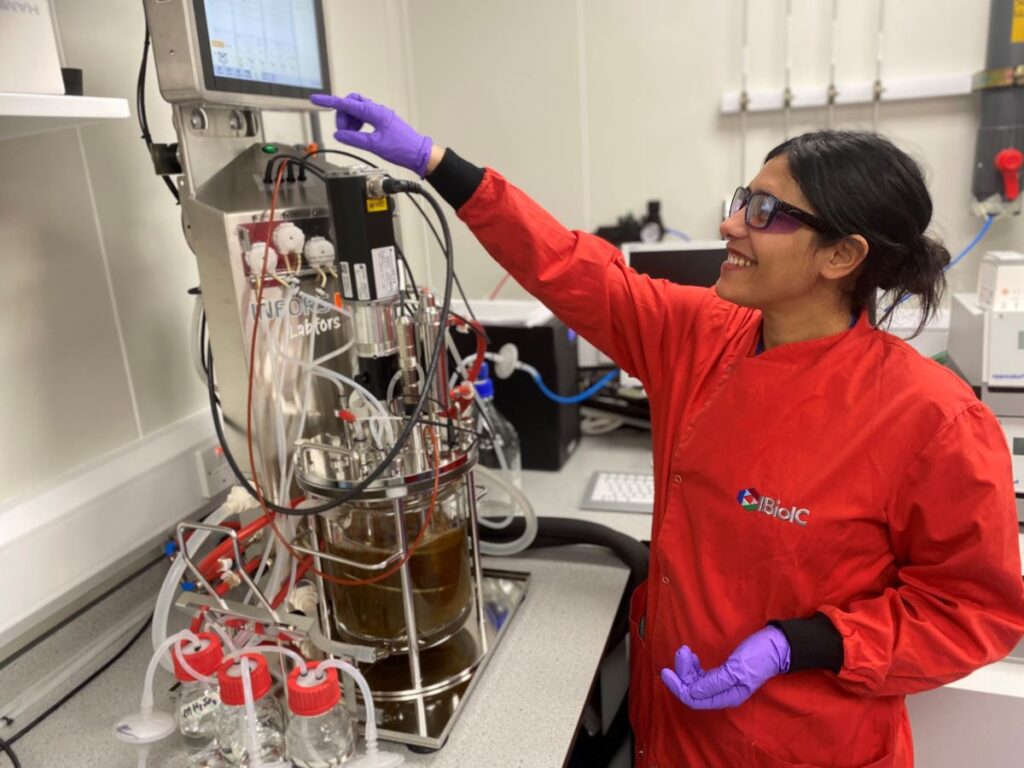

The fermenter is just part of the equipment at the FlexBio bioprocessing facility, which was created by the Industrial Biotechnology Innovation Centre (IBioIC) to provide a scale-up capability for upstream and downstream processes.

The facility’s Manager, Neil Renault, explains: “This equipment enables us to scale up from a ‘coffee cup’ scale to 30 litres. It allows us to do it in a controlled, well-understood way. Scaling up is what we do.

“It can be complex – something like a vaccine could have 14 different steps.

“People working in the bioeconomy sector generally want to do two, three or four steps. So we have equipment here that allows us to separate the useful things from the stuff you don’t want.”

Neil Renault and fermenter with seaweed

Seaweed has long been used, with minimal processing, as fuel, animal feed or even as an ingredient in human food. Today, however, it has a massive range of existing and potential uses, from pharmaceuticals to biopolymers, to replace plastic packaging.

All of these products rely on a production process that breaks the algae into its component parts. Biological agents, typically bacteria or yeasts, are tremendously effective at this and have been used in some shape or form for many centuries – to make beer or cheese, for example.

To move from an experimental stage, however, to a process that can be replicated at an industrial scale takes investment at a level beyond the means of the typical small company.

Here’s where IBioIC comes in. It was established in 2014 to fulfil the aims of the National Plan for Industrial Biotechnology, with an initial target to grow the industrial biotechnology sector in Scotland to over £900m in turnover, with over 200 companies operating in the sector by 2025. In line with its progress, this target has since been updated to £1.2bn in turnover and 220 companies.

IBioIC set up FlexBio with support from the Scottish Funding Council and the seaweed fermenter was acquired thanks to a grant from Marine Fund Scotland. The facility aims to cover its equipment and consumable running costs, and at least a significant portion of its staffing costs, from the revenue it earns running tests for third parties.

Fermenter with seaweed

The business model means FlexBio offers a service to producers and secondary processors looking to test out their approaches on a larger scale. FlexBio maintains confidentiality and does not retain any intellectual property, which remains with the client.

So what are the clients looking for?

Renault explains: “When seaweed comes out of the ocean it’s not stable, but you can combine it with fermentation to keep some of the key biochemical constituents stable. That may not be achieved in all cases by exactly the same processes.

“Some people want the sugar in the seaweed or a protein that might be converted later to something else, so it depends on the product. Fermentation has a lot of advantages when it comes to stabilising that material.

“People have been fermenting seaweed for a long time, particularly using acid fermentation, but there are other ways of fermenting seaweed.”

The FlexBio facility offers not just scale but speed. Fermentation can be achieved simply be leaving the biomass and the bacteria together in a vat for 30 days or more, but by adding other elements to the process – such as adding in air, stirring the mix, heating it or controlling its acidity – that process can be greatly accelerated.

Seaweed at FlexBio

Also, by controlling the process more tightly, it becomes possible to understand more fully what is going on and which elements or stages are necessary to reach the end result.

Pre-processing is an important step before the fermentation can start. Renault says: “We have had to buy equipment for pre-processing; blanching, washing or macerating; we have a press like a cider press to press the seaweed and get rid of any residual liquids; and we have equipment for analytics.”

It was soon clear that simply adding wet seaweed to the fermenter would not work. It needs to be cleaned of any unwanted bacteria and other material, which is where the induction pot – the vessel that looks like a big stockpot – comes in. The seaweed also needs to be reduced to a consistent particle size so it does not block the impeller.

The bacteria used in the process may be “wild” – naturally occurring on the seaweed – or it may be sourced from elsewhere. What is crucial is knowing which bacteria are involved in the process, so there is no random element.

FlexBio currently operates the only fermenting system of its kind in Scotland. There are also equivalent facilities in Norway and Belgium, for example. And the setup at Heriot-Watt could also be used for fermenting other forms of biomass, such as sidestreams from agricultural produce, for example.

Renault says demand for the service started slowly, but interest is now picking up.

Lorenzo Miele, fermentation scientist, with microscope

He adds: “The funding grants give us an opportunity to demonstrate a need and to create an awareness that we have this equipment in Scotland, and that we have the skills and expertise to help scale up new processes.

“We’ve had conversations with people where nine months ago, they weren’t interested in fermenting seaweed. They have since realised that perhaps they’ve got a waste stream from their process. There’s an element that they had not realised they could get something from, which you could find a use for if you combine it with fermentation.

“It comes down to cost of goods – what is the market for it and what would the unit price be? There’s no point in engineering a process that would cost way more than the customer is prepared to pay for the product.”

Adding seaweed to the macerator

There seems to be no shortage of new applications for this underrated crop, however. Another IBioIC project underway, involving researchers from the University of Glasgow and Marine Biopolymers, concerns combining silicon with alginates derived from seaweed to create a sustainable alternative to lithium in electric vehicle batteries.

Bioprocessing is nothing short of a quiet revolution and seaweed, humble as it is, is right at the heart of it.

This article was updated on 13 March 2024.