X marks the spot

It’s an election year for the Westminster parliament, so what is the aquaculture industry looking for from the politicians? Sandy Neil investigates

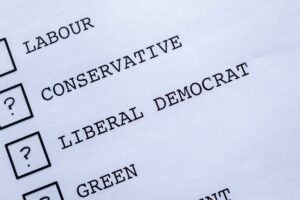

Brace yourself for a UK election year. A Labour landslide? A Conservative revival? A king-making coalition? Whatever happens, 2024 will surely become another turning point for the country and, for this short time only, we have the power to set its course.

What are the main election issues for the seafood sector? What positions do the political parties take? These are the questions we asked this month to get a clearer view of where we should head. While the industry answered with clear voices, all the main parties except the Greens responded with silence: perhaps they don’t know or can’t say yet.

In Scotland, many of the issues that matter most to the industry – such as managing fishing vessels, licensing salmon farms, building rural houses and restoring wild stocks in Highly Protected Marine Areas – are delegated to the UK’s devolved institutions such as the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood.

Other issues, such as international trade or immigration, are reserved for the UK Parliament in Westminster. The sector has a lot to say on these. Exports are vital to the seafood industry. Most of the UK’s catch is exported and Scottish farmed salmon was the UK’s top food export in 2022, with sales reaching 54 countries, led by France and the US, and totalling £578m.

Exports, and soon imports, of seafood became more problematic after Brexit

In its manifesto submission, the trade body for salmon farming, Salmon Scotland, is not alone in wanting a “smooth trade flow” post-Brexit. Specifically, it says: “The lack of a new eCertification for export health certificates (EHCs) and issues with the current outdated system is costing salmon farmers millions of pounds every year. Improving the certification programme should be an urgent priority for Defra.”

Salmon Scotland also would like “a more enlightened approach to the movement of labour into the UK, which recognises the unique challenges our coastal and rural farming communities face, including a change to key worker definitions and a broader public signal that the UK is open to people coming here to work”.

Salmon farming directly employs more than 2,500 people in economically fragile coastal communities in rural Scotland, it says, with a further 10,000 Scottish jobs dependent on the sector.

So we’re just a few lines in and already we can see how much is at stake in this Westminster election, which Prime Minister Rishi Sunak expects to call “in the second half” of 2024, before the deadline on 28 January 2025. The result may also be a bellwether for the next Holyrood election due on 7 May 2026.

At this early stage, it may be wise for the sector to appeal to all.

Seaweed farm

The green stuff

“Seaweed has the great potential to provide benefits to all the major political parties,” said Rhianna Rees, the Scottish Seaweed Industry Association’s Business Development Manager.

“For the Green Party, seaweed is a nature-based solution, providing ecosystem services and… protection over Marine Protected Areas where fishing should not be taking place. For the SNP, seaweed is part of a strong marine sector that has a firm and direct history in Scotland, providing a product with strong provenance credentials. For the Labour Party, the seaweed sector could open up more opportunities for jobs in coastal communities and for the Conservative Party, seaweed provides further blue economy potential and general economic growth.

“By focusing on scalability, the recognition of marine natural capital and environmental research on ecosystem services provided by the seaweed sector, we should be able to unlock some of seaweed’s enormous potential.

“It is one of the most sustainable products on the planet, it requires no feed, fertiliser or freshwater, and the UK has an extensive coastline that we could be utilising for the seaweed sector. We need to reduce the cost of production substantially and to do that we need to simultaneously increase mechanisation and scale. The UK would need to invest heavily in scientific research to determine both the positive and negative impacts of seaweed cultivation at scale in multiple locations, including nearshore and offshore.”

Rees adds that her members would also like to see pilot projects in offshore wind colocation projects, similar to the ones seen in Belgium and Denmark.

Voting

She explains: “These colocation opportunities could provide a potential solution to the marine spatial squeeze felt by the aquaculture sector and biodiversity net gain goals imposed by the government. With rigorous scientific data supporting the biodiversity credentials of seaweed, we could unlock a previously untapped area whilst providing consenting support to another sector.

Rees adds: “Infrastructure investment is a key bottleneck and needs to be addressed. Processing is critical to success as buyers want their seaweed ‘stabilised’, for example, dried, frozen, ensiled, fermented. Kelp farmers who cannot access sufficient processing facilities within their start-up years will likely fail. We have seen this addressed in other countries, with many lessons to learn from Norway, North America and the Faroes. With funding into, and the encouragement of, knowledge exchange we could help provide and focus on low-energy, low-cost, local processing. All of which should be reflected in new marine policies.

“Finally, routes to market. There are 101 different things you can make with seaweed and a new use every day. However, with different products come with major differences in the price and scale of seaweed required, and many routes to market will not benefit kelp farmers because their price point for raw materials is too low (for example, bioplastics, biofuels). We need to decide (as a nation) what markets will deliver most prosperity for seaweed farming businesses (for example, biostimulants, food, nutraceuticals) and from that invest in developing those markets, with support from government and policy.”

Ballot paper

What shellfish farmers want

Meanwhile the Shellfish Association of Great Britain’s Chief Executive David Jarrad wants the next government to deal with issues constraining the industry, such as the use of Gigas oysters, “the mainstay of the oyster industry in the UK”.

“Currently, it seems government and its agencies are actively trying to prevent new areas being cultivated and expansion to existing farms, and are vilifying the use of the species,” Jarrad said. “This is against a background of government bringing the species in (1960s) and that science suggests they will spread naturally all around the UK coast by 2050.”

A second issue is pollution. “The UK is recognised as the dirty man of Europe,” he explained. “Our shellfish harvesting waters are ‘protected’ by mandate under the water framework directive – but 75% of our waters fail this standard. The ambition that 50% of our waters should be improved by 2050 isn’t overly ambitious!”

A third is trade with the EU, he added: “For many decades, the EU imported Class B shellfish from the UK. But since Brexit this has been disallowed. A new SPS [Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures] arrangement needs to be found to reinstate this trade.

“The classification of shellfish growing waters is carried out by the Food Standards Agency under the same regulations and directives as when we were in the EU. But it is applied differently to our European neighbours, who apply them in a much more industry-acceptable manner whilst protecting consumers.”

Would a change of government mean a reset for UK-EU relations?

Targeting trade issues

Improving trade with the EU and easing the passage of perishable products to overseas buyers is also a priority for Seafood Scotland, the national trade and marketing body.

“Thanks to the valiant efforts of the industry to adapt to the post-Brexit landscape, worldwide demand remains high, but it is also true that measures to smooth trade flow and open new markets have been slow to materialise,” says Seafood Scotland’s Industry Engagement Manager Jeni Adamson. “The issue of EHCs is a case in point. It is widely accepted that, in their current form, they place an undue burden of paperwork on UK exporters, particularly for smaller businesses.

“Hopes rose when a pilot programme to test eCertificates got underway. The pilot went down well with the industry owing to its potential to support export growth and generate millions for the Scottish and UK economies, but it was halted without clear plans for adoption.

“So we will be continuing to press both UK and Scottish governments to help resolve any stumbling blocks. We believe digital EHCs are the way forward for an industry that sustains thousands of jobs and supports the livelihoods of so many of Scotland’s coastal and rural communities.”

YouGov voting intention polls, asking “If there were a general election held tomorrow, which party would you vote for?”, have consistently put Labour ahead of the Conservatives since December 2021. Give or take a few here and there, the party is about 20 points ahead since Mr Sunak became PM in October 2022. So, barring unexpected events, we’re probably looking at the Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer, becoming Prime Minister. Does he want to improve trade with the EU? Can he?

Starmer hopes to achieve a “much better” Brexit deal. He said his party would use the review of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) to expand its terms. He said the current trade deal with the EU is “too thin” and that its scheduled review in 2025 should be used to create a “closer trading relationship”.

Labour has proposed a number of measures to add to the EU deal, including an agreement on veterinary standards and improved labour mobility arrangements. Labour is willing to go further than the Conservatives in signing supplementary agreements to ease post-Brexit friction in specific sectors such as food imports.

However, the EU considers the TCA “a very good agreement”. There is also significant Brexit fatigue in EU circles as well as a long list of higher priorities, whether energy, Ukraine, de-risking China and the migrant crisis within the EU itself. There is little appetite to revisit the TCA. Therefore, should Labour come to power, it will need to persuade the EU to negotiate.

There will be a lot at stake this year and we can expect all these arguments to be well rehearsed over the coming months.