Taking on the challenges

Climate change and other factors keep throwing up new threats to fish health, as our expert panel explained in Fish Farmer’s Aqua Agenda webinar. Robert Outram reports

THE PANELLISTS

Dr Iain Berrill

Dr Iain Berrill Head of Technical, Salmon Scotland

Dr Iain Berrill has always had an interest in the marine and freshwater environment. He studied a BSc in Marine Biology at Swansea University, followed by an MSc in Applied Fish Biology at Plymouth University and a PhD at the Institute of Aquaculture in Stirling.

He has worked with industry body Salmon Scotland (formerly the Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation) since 2010. He sits on various industry and governmental working groups, and acts in a steering group and advisory capacity on several collaborative research projects.

Charles Allan

Charles Allan Head of the Scottish Fish Health Inspectorate

Charles Allan has been involved in the Scottish aquaculture industry in both commercial and statutory roles for more than 30 years, including working in a small commercial salmon company, Scotland’s Fish Health Inspectorate and the Marine Laboratory in Aberdeen.

He has led the Fish Health Inspectorate since 2008 and in 2022, took on additional responsibilities as Senior Delivery Lead for Aquaculture and Fish Health, Freshwater Fisheries and Biosecurity.

Charles Allan is currently responsible for delivery of all the scientific work of staff, covering aquaculture, fish health, salmon and freshwater fisheries, and biosecurity. This is within the science, evidence, data and digital portfolio of the Marine Directorate of the Scottish Government.

Ronnie Soutar

Ronnie Soutar Head of Veterinary Services, Scottish Sea Farms

Ronnie Soutar has been involved as a vet in aquaculture for more than 35 years. He is currently employed as Head of Veterinary Services for Scottish Sea Farms, one of Scotland’s leading salmon farmers.

He holds a Master’s degree in Aquatic Veterinary Studies from Stirling University and is a Past President of the Fish Veterinary Society. He represents fish vets on the Scottish Government’s Farmed Fish Health Framework working group and is a member of the Veterinary Products Committee, advising the Veterinary Medicines Directorate on medicines issues in aquaculture. He is also a former Chair of animal welfare charity the Scottish SPCA.

The discussion was facilitated by Robert Outram Editor, Fish Farmer

Fish Farmer’s first Aqua Agenda webinar focused on a key issue for aquaculture: fish health and welfare in salmon farming.

This is always high on the agenda, but the last couple of years have brought greater public attention and some criticism for the aquaculture industry in Scotland.

Mortality figures in 2022 and 2023 have been challenging for the industry, both as measured by harvest numbers and profitability, and in terms of reputation.

The Aqua Agenda Fish Health and Welfare webinar brought together a panel of experts to discuss the challenges, the factors behind them and what the industry has learnt.

They were:

• Dr Iain Berrill: Head of Technical, Salmon Scotland;

• Charles Allan: Head of the Scottish Fish Health Inspectorate; and

• Ronnie Soutar: Head of Veterinary Services, Scottish Sea Farms

Salmon being examined

As Dr Berrill explained, Salmon Scotland does a lot to help the industry address fish health and welfare issues, including running health managers’ meetings, networking and engaging with health managers, organising technical events and supporting research.

Salmon Scotland also provides secretarial support for a Prescribing Vets Group and helps the industry with its transparency agenda, for example in its reporting of lice data in various forms since 2010.

Berrill said: “In the last two years, we’ve seen some challenges and our sector has been open about those. Our mortality rates have been compared to other sectors and I would make two observations. We are the only sector in the UK to publish mortality data on a farm-by-farm basis. I think globally, we are the only salmon farming sector to do that.

“But more importantly, we have to remember that salmon are a completely different species and fish are a different class of animal to birds and mammals, which are traditionally farmed.

“We have an animal that produces thousands of eggs with the hope that a couple will go on to survive and reproduce. Birds and mammals have different strategies. Our fish have different physiologies, too.”

Soutar highlighted that there is sometimes a disconnect between real and perceived issues. As he put it: “I don’t spend a great deal of my time these days thinking about sea lice – but if you listened to wider social media, you would think that was the biggest thing happening.

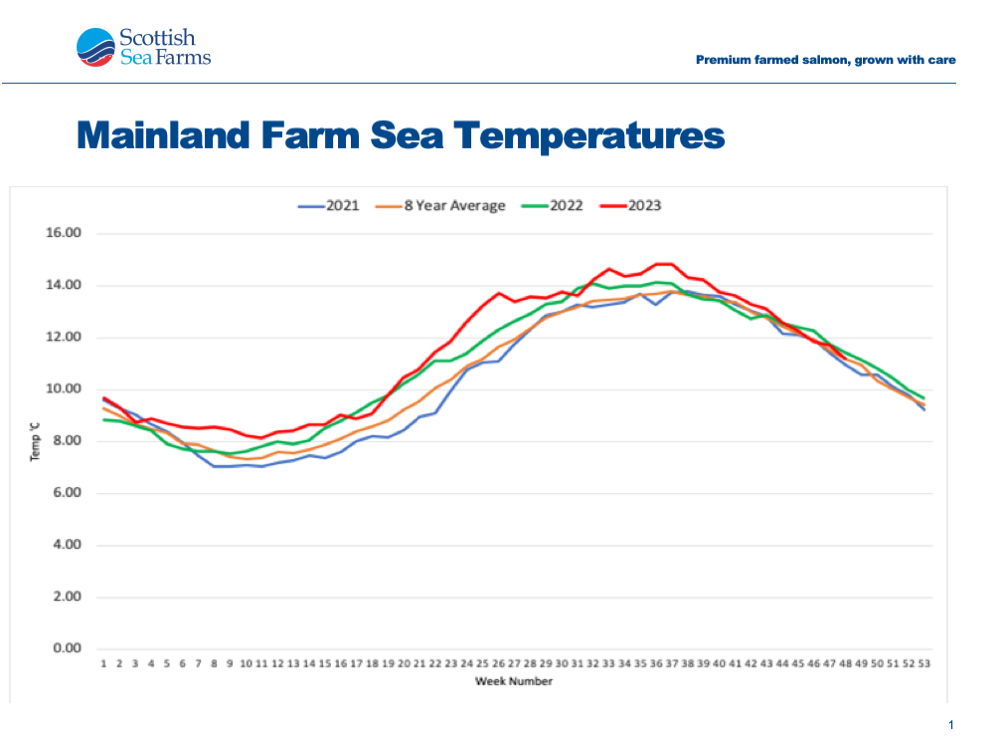

Sea temperatures from 2021 to 2023 (source: Scottish Sea Farms)

“I do spend a lot of time thinking about gill health, which I think represents around 50% of what’s affecting the fish I care for.”

And he pointed out that on any given day, the vet team at Scottish Sea Farms have around 20 million fish under their care.

Soutar shared a graph showing mainland sea farm temperatures recorded by his company between 2021 and 2023. He noted that 2021 had followed the average pattern but 2022 and 2023 had been warmer, with winter temperatures in the early part of last year never dipping below 8°C.

He added: “Those temperatures are well within the preferred range for salmon – they won’t suffer directly as a result of those temperatures – but there is an impact on everything else: the pathogens, the parasites, all the organisms that can impact fish.”

He added: “Predation has certainly been a factor. We’ve seen some regulatory changes affecting seals, that in my opinion have had a direct and negative effect on fish health and welfare.”

It is now unlawful in Scotland to use lethal force against seals or even manhandle them. Use of acoustic deterrent devices has been suspended.

Soutar stressed: “I am firmly of the opinion that our response should be and is concerned with husbandry and farming strategies, not about ‘treatments’. Prevention is better than cure; how we manage and handle our fish is significant.”

The first question for the panel was: how much do the primary causes of fish mortality change, year on year?

Dr Berrill argued that the change had been significant. The 1990s had seen different challenges compared with the 2010s, when issues like amoebic gill disease (AGD) started to emerge. More recently, the industry has also had to address issues such as harmful algal blooms and micro jellyfish.

Allan noted that interventions have changed. In the early days, the farmers faced problems such as furunculosis and sea lice. Vaccination has had a significant impact on the former and a number of treatments have been developed for sea lice.

Fish farm, Scotland

He added: “Other pathogens emerge. I would characterise the 1990s as dominated by viral diseases – but the pharmaceutical industry stepped up and we had a wider range of vaccines.

“From the earlier part of this century up to now, we have seen the emergence of a number of pathogens which previously weren’t of such concern.”

Soutar agreed that both the challenges and the responses had evolved: “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about sea lice – but

I do spend a lot of time thinking about the effects of controlling sea lice. We do control them well now, but the controls have an impact themselves.

“Gills will heal, given a chance, but if we have to deal with sea lice even at a level that may not be harmful to the fish, that may have an impact on gill health.”

Returning to the issue of seal predation, he added that farmers are strengthening nets where there is a risk of seal attacks, but he stressed that simply keeping seals out of the pens is not enough. Even the presence of large predators nearby is enough to stress the fish. This has been linked to impaired immunity and an increase in viral diseases.

The panel also discussed climate change as a factor and in particular a question from the audience: “From a fish health perspective, do current climate change-induced environmental challenges now point to an inevitable need for a more fundamental change in how and/or where salmon is farmed in Scotland, rather than just another layer of costly treatment options? If so, what might this look like?”

Soutar commented: “I don’t believe the temperature itself is an issue for the salmon, but it has an effect on everything else, which can have an impact on fish health.”

He pointed out that in 2018 – the year of the winter blast that became known as the “beast from the east” – Scotland experienced a very cold winter and the summer was not especially warm. Fish survival that year was good, Soutar added.

He said: “The relationship between winter temperatures and fish health is just as important as the peak summer temperatures. In mild winters, organisms in the sea survive better.

“The pathogens – such as the amoeba that cause AGD – survive in larger numbers. And organisms, like jellyfish, that were previously known in the Mediterranean or the English Channel now have a wider range.”

Whether this represents permanent climate change or a cyclical phenomenon, we will have to see, he added.

Berrill pointed out that the salmon farmers are already exploring different strategies to the way fish are farmed to address climate-related issues, from semi-closed and closed containment systems to siting farms in more exposed locations.

Sea lice

He stressed, however, that such decisions “…have to be driven by data and experience.”

Are Scotland’s fish health challenges unique or are they shared by other countries? It’s a bit of both, the panel felt.

As Dr Berrill stressed that even Norway alone has a long coastline spanning a range of latitudes and different regions are facing different issues.

Scotland shares a number of issues with other north Atlantic salmon-producing nations, such as Norway, Ireland, Iceland and the Faroes.

Even on the other side of the globe, Tasmania for a long time faced challenges with AGD, which was not initially a problem for the north Atlantic – but has increasingly become one.

Allan stressed the importance of sharing information internationally, especially clinical data between reference labs.

Scottish Sea Farms is jointly owned by two Norwegian companies: SalMar and Lerøy. This creates a cross-border platform to share information and best practice within the business.

Soutar observed: “The international ownership of salmon companies in Scotland sometimes attracts negativity, but for us it’s a major positive.”

Having said that, he also stressed the importance of tailoring farming approaches, nutrition and genetic selection – which has become an increasingly important tool for farmers – to the requirements of salmon in specific locations rather than relying on a “one size fits all” approach.

The panel also addressed a question about stress. One answer to health and welfare challenges in the late 1980s and early 1990s was “low stress” farming – but are today’s farming methods low stress?

Ideally, farmed fish thrive best with a minimum of handling, but interventions are required – such as treatments for lice or gill disease – that in themselves can create stress and so weaken the fish’s immune defences.

Soutar said: “The armoury of medicines we have is limited, but physical interventions are effective. They are a necessity, but sometimes we have to use them because sea lice levels have risen to a number that has been specified, not for the benefit of the fish that have the sea lice on them but because of a perceived benefit elsewhere.

“Sometimes I find myself having to do things that go against my principle of ‘first, do no harm’. So, I think we have to look at our interventions and when we are compelled to use them.”

Dr Berrill agreed and added: “There is also a need for regulatory support so we can have diversity in where and how we farm our fish. Companies can use their years of experience to understand where and when fish should be in different places.”

Allan pointed out that dialogue does already exist between fish farmers and regulators, for example through the Farmed Fish Health Framework. He said: “We are always engaged in trying to make the lot of the profession better.

“We farm our fish differently [compared with the early days]… We have more knowledge with regard to risk assessment and this has moved significantly forward since the early days of the industry.

“There has been some really significant work done on fish welfare.”

Stocking densities are also lower than they once were, he added.

Another question concerned cleaner fish – they do an important job in helping to manage sea lice, but are we monitoring their health and welfare sufficiently?

Allan made the regulatory point that cleaner fish are aquatic animals that are stocked in fish farms and therefore fall within the realm of the aquaculture regulations.

He said: “They are valuable, they are well looked after but there are certain issues surrounding their use.

“There is a difficulty in accounting for them, particularly at the end of a cycle. They do a good job, but… we don’t necessarily understand the fate of all the fish. That is something that can be addressed.”

Dr Berrill commented: “As with salmon farming, there are always improvements that can be made. Cleaner fish species are relatively new in aquaculture and the speed of learning has been very, very rapid.

“There has been investment – not just financial but in terms of time, effort and commitment – to ensure, for example, there is a lumpfish or wrasse specialist on any farm that uses cleaner fish.”

He added that Salmon Scotland is currently financing a PhD student who is researching the catching of wild wrasse as cleaner fish to assess the sustainability of the practice.

Ballan wrasse

Two other questions concerned the use of bubble curtains (aeration) to protect fish against harmful algal blooms and micro jellyfish, and the potential value of artificial intelligence (AI) and underwater cameras to monitor fish health and welfare.

On the former, Soutar confirmed that bubble curtains are already being applied in Scottish farms.

For AI, Dr Berrill said: “This is a hugely interesting area, but we need that information to be appraised by an individual. We can’t automate decision making.”

There is no substitute for stockmanship – the insight of an experienced farmer – he stressed.

Soutar agreed that this technology is a game-changer: “I could learn more sitting at this desk and looking at the fish through underwater cameras than I could by standing at the surface looking down at the fish… but it does come down to people. What we take from the data and what we do with the data is vastly important.

“We have some excellent people involved in fish farms in Scotland and that, of all things, gives me grounds for optimism.”

You can watch a recording of the Aqua Agenda Fish Health webinar in full at: bit.ly/AquaAgenda-health

Ideas for future Aqua Agenda topics are welcome. Email Fish Farmer at editor@fishfarmermagazine.com